Sitting in my car, I wasn’t sure if I should do this. I can’t remember my exact thoughts but I do remember the uncertainty. I’d been experiencing that at work too. Decisions were harder to make and I was less sure of what I should do. I knew it wasn’t usual for me as I had been very focused throughout the project I was working on. The tight timescales had meant I had been making decisions every day. Several decisions each day in order to keep us moving in the right direction and achieve the project’s aims.

Taking a deep breath, I made the phone call to book an appointment. And yet, when I saw my GP, I didn’t want him to sign me off sick for a whole month. Looking back on it now, I can see my anxiety was hindering my decision-making, making me second guess my instincts. We compromised on 3 weeks, although deep down I think I knew I’d need longer.

I can remember thinking that if I had broken my leg, I wouldn’t be debating with myself whether or not to see a doctor. With mental health, it was different, less clear-cut; how stressed do you need to be to need to see a doctor? There was also the fear of admitting to myself and others that I wasn’t coping when I felt I should be able to. And my job description told me that I should be able to; resilient was an essential criterion in the person specification. So here I was, stressed about admitting I was stressed.

I did know that it wouldn’t come as a surprise to my immediate colleagues. I had been crying more and more frequently at work. To start with in the relative privacy of the toilets, but then in several meetings and finally to the point where one Thursday, I felt like the flood gates had well and truly opened and I had found it difficult to stop. While in a meeting at a breakout table in the middle of the open-plan office. They didn’t know that I’d also woken up sobbing the following day and realised there was no way I could hold it together if I went to work that day.

It wasn’t until the following Wednesday that I made the GP appointment. And that was largely prompted by a passing comment a colleague had made which was reiterated by a relative. More as tactical suggestions, a way to take back some control over the situation, rather than as a way of getting support. But they helped me realise that maybe I did need support. Something needed to change. I definitely needed time out.

My manager later described the situation I had found myself in as the “perfect storm”. Not only were the difficulties associated with the project I was leading escalating and largely outside my control but I and the rest of my team were being made to re-apply for our own jobs; a process that completely conflicted with my values and threatened my identity.

Although the increasing stress over several months and the time needed to recover were horrible to experience, I learnt a lot about myself along the way. And it has made me more empathetic and attuned to the wellbeing of my colleagues.

It is important to recognise that resilience is a state, not a fixed trait. We all show different levels of resilience in different situations and at different times. For example, I think most people’s ability to cope skilfully with difficulties decreases when they are tired. It is therefore misleading to describe people as either resilient or not. As a changeable state, we need to take action to build and maintain our resilience.

“Resilience is a life-long journey. None of us can claim it as a permanent state.”

Kathryn McEwen [1]

So, what was happening to my resilience in the face of these threats and pressures?

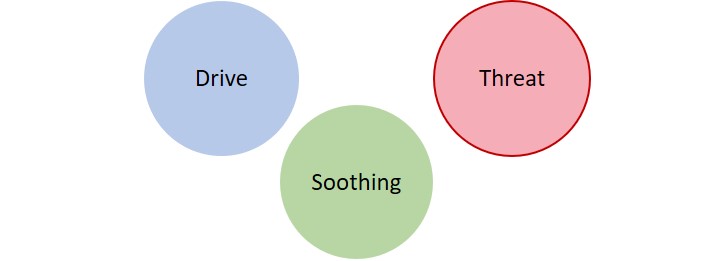

Paul Gilbert[2] describes 3 emotion-regulation systems:

The threat system is associated with anxiety, frustration and anger. It is activated by external threats, but also by self-critical thoughts.

The drive system is associated with motivation, energy and positive feelings so that we will seek out the resources we need. However, if our goals and desires are blocked, this can be seen as a threat, activating the threat system.

The soothing system is associated with contentment; being happy with the way things are, feeling safe and loved, with a sense of inner peace. This system is activated by being compassionate and kind to yourself and others.

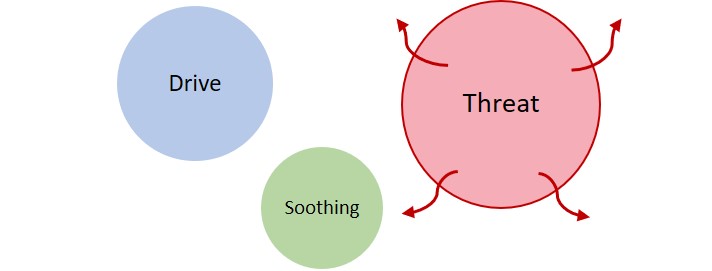

We function most happily when the 3 systems are in balance. But at that time, mine were not:

My drive system was over stimulated. I was extremely passionate and focused, striving to successfully deliver project aims and make a difference. My sense of identity also became entangled with the success of the project. Feeling that I had done a good job was integral to my self-worth.

This contributed to the growing stimulation to my threat system. External pressures and challenges mounted, jeopardising project success and threatening my sense of having done a good job. I started blaming myself for things outside my control, feeling I could have done more. In this situation, how would I be able to perform well in an interview for my job?

I had paid no attention to my soothing system for months, not really aware of its existence. As I strived to deliver the project, I regularly worked long days, sometimes 6 days a week, often not stopping for lunch. I sacrificed hobbies and my social life as work seemed more important. I was exhausted.

My job was not “just a job”; the rest of my world had shrunk.

[1] McEwen, K (2018). White Paper: Resilience at Work, A framework for Coaching and Interventions. Working With Resilience consortium.

[2] Gilbert, P (2009). The Compassionate Mind cited in Mindfulness Based Living Course 8 week programme course manual (2011), the Mindfulness Association

This is an excellent piece about resilience. You’re right, it is a changing state and it’s definitely so much harder to be resilient when you are tired. Very thought -provoking.

LikeLiked by 1 person